Día de Muertos (Day of the Dead) 2023

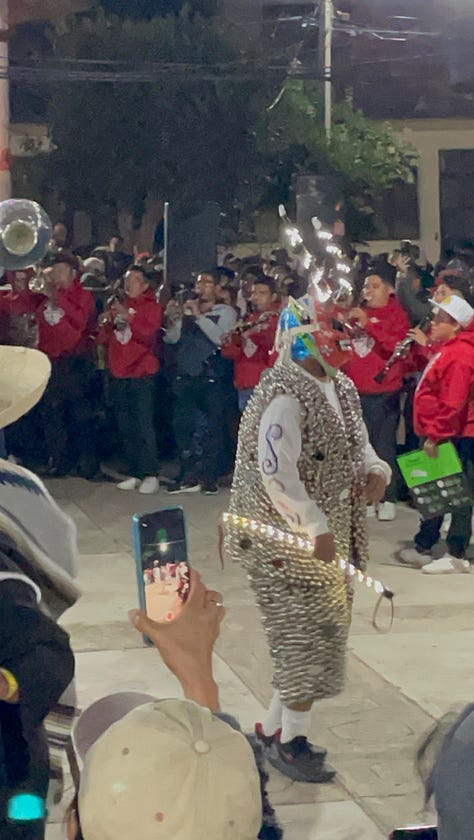

A close-up view of this year's Day of the Dead festival.

Mexico is a country that loves a celebration, a fact that was unexpectedly reinforced in August. Because of my work schedule Andrea had to come to Mexico alone to purchase our home while I stayed in New York, and I looked down at my phone one afternoon to find that she had sent me text and video from Oaxaca de Juárez (the city) of an ongoing parade for Día del Taxistas (Day of the Taxi Drivers).

This is not a thing that would happen in NYC, and I think it reflects not just that people value taxis here (which are a real phenomenon I’ll write about another time), but that people also love any excuse to dress up, parade around, and have a party.

This particular time of year has two big holidays. One, no surprise, is Christmas, which in Mexico is called Navidad. The other is Día de Muertos, the Day of the Dead.

What is Día de Muertos?

Día de Muertos, which is also just called Muertos, is a Mexican holiday which combines indigenous traditions (in this case they’re said to be Aztec) with Christian ritualism and imagery. There’s also a healthy dose of Halloween thrown in. You’ll see crucifixes, and you’ll see an astronomical volume of spiritually-significant flowers, but you’ll also see people dressed up as undead nuns and evil clowns.

Muertos is, unequivocally, a celebration, and one which has two relatively separate components. One takes place in local homes and cemeteries, and the other takes place on the streets.

If you’ve seen the Pixar movie Coco you’ll have a pretty solid grasp of the basic concepts. The idea is that after people die they enter the afterlife, and their spirits can be encouraged to return home during Día de Muertos, a day when the barrier between the land of the living and the land of the dead is particularly thin. An ofrenda (an alter) is set up featuring photos of the deceased and is laden with sweets like pan de muerto (bread of the dead), Calaveras (skulls made from sugar) or favorite foods and drinks of the deceased. Flowers like cempasúchil (marigolds) and terciopelo rojo (cockscomb, a type of celosia) are placed on and around the ofrenda, and the scent of the cempasúchil is said to reach the land of the dead, to guide people back home. The ofrenda is often, but not always, stacked in tiers, sort of like a pyramid.

Sometimes there will be musicians present in the graveyards, and a friend from the U.S. who has been to a muerteada graveyard said one year she saw a full rock band set up. But, in general, it’s a semi-private, candlelit affair not really suitable for tourists.

But the other side of the experience is the town party.

The Muerteada Party

In Mexico, Día de Muertos is a big deal. In Oaxaca, Muertos is a very big deal. In our pueblo (town) San Agustín Etla, it’s a huge deal.

Here are things I learned about Muertos in our town:

San Agustín Etla is so famous for Día de Muertos that tour companies used to bring in tourists via coach busses.

So many people attend that the roads are closed starting at 4pm, and only locals can get in and out. This of course doesn’t really stop tourists from coming in: last night there were people with tour badges and giant telephoto lens cameras, dinguses with drones, and all manner of gringos and visitors.

But traffic is so bad that getting in and out isn’t even really an option. Once things really start rolling you’re basically stuck here. And there are so many people trying to get in that enterprising home owners have put up big signs, in both Spanish and English, advertising available parking.

It’s also a bad idea to try to leave because of drunk drivers, and because of people passed out in the street who you might accidentally run over (or so we were told).

The party begins at around 9pm on November 1st but doesn’t really kick off until midnight, and ends around noon the next day. As I write this it is 12:10pm on November 2nd and the brass marching band is still blasting away in our barrio’s town square.

The party, a parade called a comparsa (which is part of the “Muerteada” celebration) moves from barrio to barrio in what is, in essence, a rolling bacchanal where everyone is dressed like skeletons, corpses, and demons. The comparsa will stop at designated houses for treats and mischief. This blog entry says the Muerteada allows the spirits of the dead to inhabit the bodies of the living, allowing them to literally join the revelry.

A common costume involves covering—covering—a person in shiny bells so that when they move there’s a distinct jingle.

The Muerteada is such a big deal that the local brass marching band has been practicing, loudly, in range of our house, every single day for the past three months.

In our town a hyper-local play (which largely makes fun of the mayor and local elected officials) takes place. Unless you are intimately familiar with the intricacies of local government, it is both inscrutable and rather boring. It is also long. This is a Festivus-style satirical airing of grievances.

You can get a can of beer, street side, for a dollar or less.

There are fireworks, which are set off about four feet away from revelers, with literally no barrier between the launchers and the people. What could go wrong!

All In On Día de Muertos

Día de Muertos is an important day both culturally and for tourism. Even before we knew we wanted to move to Mexico it was a celebration I wanted to experience, and it truly doesn’t disappoint. The degree to which both tourists and locals embrace the revelry is really wonderful, and both the government and businesses put a lot of money into making sure the city (Oaxaca de Juárez) and all of the towns are decked out.