"They're going to be an interesting kid."

Our friend Eli was the first to find out we're pregnant and his reaction didn't disappoint.

The first person to learn about our pregnancy was my childhood friend Eli and after congratulating me he made sort of a rueful chuckle and said, “they’re going to be an interesting kid.”

Eli’s reaction immediately made me think of an outtake from Seinfeld, where Bryan Cranston (playing dentist Tim Whatley) cycles through a variety of facial expressions and noises in response to seeing Jerry’s unexpectedly unattractive date, cracking up Seinfeld multiple times during the filming of the episode.

Everyone I’ve described Eli’s reaction to has also laughed, I think in large part because it carries just the slightest edge. The implication is clearly that we’re kind of weird people and that the kid will inherit and reflect our peculiarities. I wasn’t even a little bit insulted, though, and instead was tremendously pleased. I hope the kid is interesting. How could they not be? If we, a writer/editor/cook and a government/non-profit wonk produce a white kid who we raise as a culturally-blended Oaxacan American and they end up being unremarkable, I’m not sure I’d ever be able to forgive myself.

Eli found out about the pregnancy far too early because at the time we told him we didn’t know just how little time had passed.

In a previous entry for paid subscribers I wrote that we had purchased a bulk package of pregnancy tests that look exactly like at-home covid tests, small strips of paper that you dip into pee and which, if positive, produces a result of two solid lines. We were so shocked we were pregnant, and so excited, I ended up texting Eli a photo of the testing strip mere minutes after we saw the result.

He wrote back, “Oh jeez, do you guys have covid again?” to which I replied, “look more closely at the strip.”

His reaction came a few minutes later, along with a phone call. The bottom of the strip clearly displayed the word “PREGNANT,” and after we discussed the news I told him that we hadn’t even had the test results confirmed yet and that we needed to visit a doctor to be sure we didn’t have a false positive in our hands. That same day we found a doctor and made an appointment, and a couple of days later found ourselves sitting in a clean, upscale office in the Reforma neighborhood of the city.

The waiting room of the office was not so different from what you’d find in the U.S. Most of the women who came in were there with a male partner, who ranged from being excited and affectionate to checked out and perhaps not hugely invested in their partner’s pregnancy. At one point a young teenage girl came into the office and sat looking glumly uncomfortable next to a woman who was clearly her mother. Later in the car when I asked Andrea if perhaps the girl had gotten herself into a little bit of trouble Andrea rolled her eyes and said, “no, she was getting birth control!”

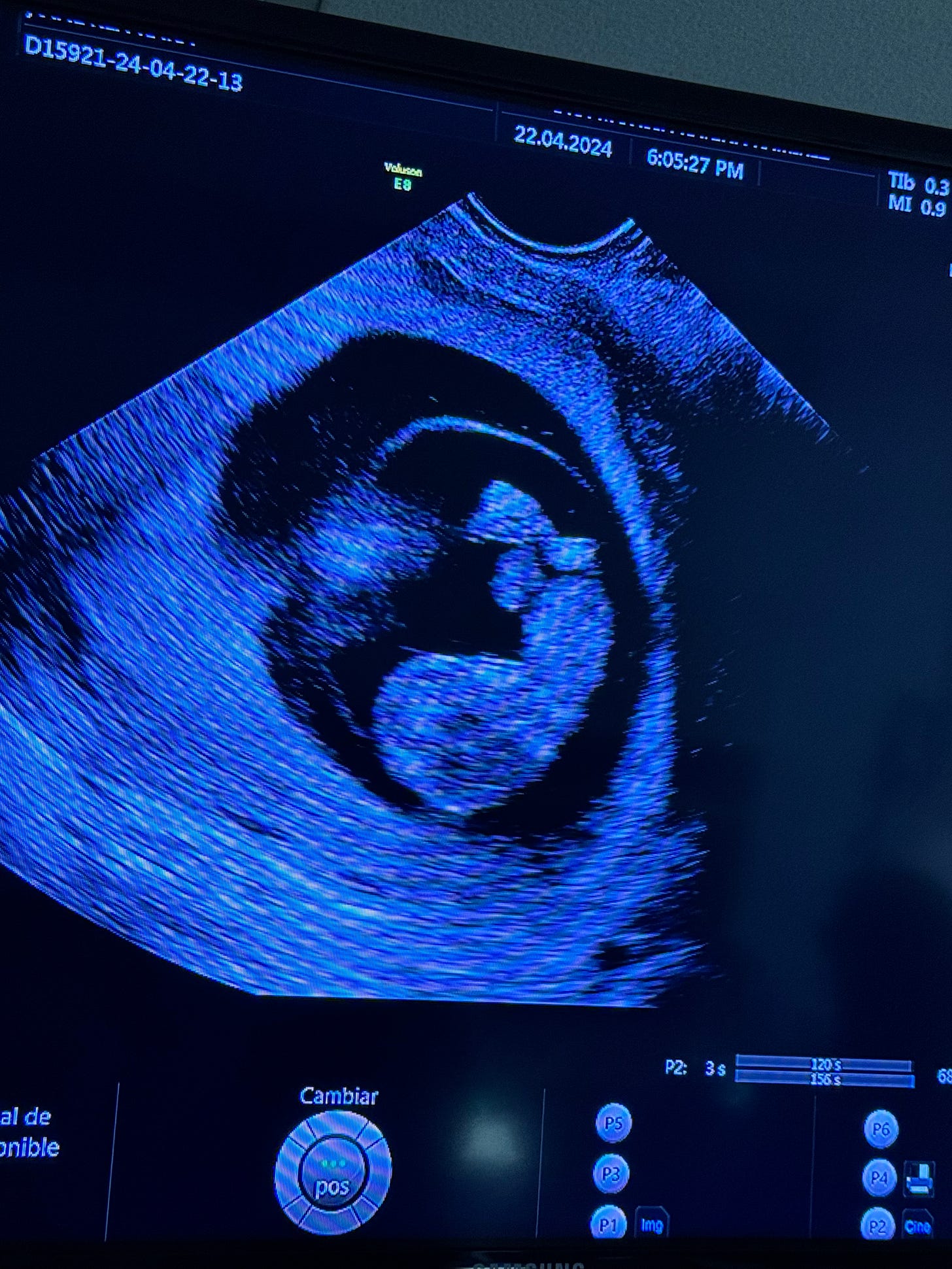

Soon the doctor called us in and just a few minutes later Andrea was in an adjoining examination suite receiving an ultrasound. The results were conclusive; we were definitely pregnant. But, somehow, we’d caught the pregnancy at what is effectively the earliest possible moment someone can even know that they’re pregnant, the four week mark.

Several times on Instagram I’ve been served a video showing a six week-old baby (the age at which American abortion bans start) in utero, its body clearly formed and its arms and legs moving. The video is seemingly AI-generated and likely was made for pro-life political purposes. Reality is far different from what is pictured on social media, and our doctor explained at our next visit two weeks later that at six weeks “el feto tiene uno centímetro,” meaning it had a length of a single centimeter. The fetus, the doctor said, was the same size as a grain of rice.

We didn’t realize The Rice, as we’ve been calling it, was so early in its existence, and it dawned on us we’d need to keep it a secret for a considerably longer amount of time than we’d thought.

I am already 40 and Andrea turns 40 soon, entrenching us firmly in the insultingly-named “geriatric pregnancy” category. Not only would we need to wait 12 weeks before we told people, the standard amount of time it’s recommended people wait before they let others know about a pregnancy, it would also be a good idea to delay any announcement until we’d completed genetic testing and had a 3D ultrasound. As I said to Andrea, we needed to make sure that the baby was healthy and not actually just a giant salamander. By telling Eli and his wife Brandi so early we hadn’t just dialed them into our huge life event, we’d made them confidants.

How we feel about being parents in Mexico is a subject better saved for other entries here. In many ways it is considerably easier to be a parent in Mexico than in the United States. Culturally, Mexico is far more accepting of children and of parenthood than a great many places in the U.S. Because of our income level a private school education is easily accessible to us. Medical care here can be excellent if you select a good doctor and go to a private hospital. We can easily afford childcare. And, ever on my mind, Mexico doesn’t have school shootings.

But there is something peculiar about the idea of raising a child in another country, as grateful as I am that that country isn’t the United States. We’re permanently tethering our future child to a place we are only just beginning to understand. I worry about the degree to which they’ll be welcomed here, and in which ways they’ll be othered. And even though Mexico is increasingly, curiously progressive, if they’re gay or trans they undoubtedly face a higher risk of persecution and violence than they would if they lived in one of the U.S.’s liberal states.

For now, though, we will navigate the first steps. More doctor’s visits, finding a Spanish-speaking online doula, taking online parenting classes, preparing our home for the baby’s arrival. And, of course, picking a name.

Congratulations on baby salamander 🫶🏽🌈💃!

Felicidades y muchas bendiciones!