Author’s Note: For the next year I’ll be writing The Oaxaca Postcard Project, where every day of the year I’ll be sending a postcard, free of charge, to a different subscriber. Paid subscribers will receive their postcards first. If you’d like to receive a postcard please sign up using this form.

The election of Claudia Sheinbaum came and went in a blur, and, beyond its historical significance, it was largely an unremarkable day save for one thing: her ascendency to the presidency made it almost impossible to buy lunch.

Lunch is both a ritual here and a part of Edgar’s compensation (please see: Almuerzo For Edgar). When I was working as an editor at Serious Eats I took lunch so seriously that I developed a bit of a reputation. Most of my job involved editing and data analysis and the act of cooking proved to be a good way to clear my head during my half-hour lunch break. While many of my coworkers found themselves eating leftovers or some variation on the Sad Desk Lunch, virtually every single day I would make a hot lunch, from scratch, for myself and Andrea.

I’ve continued the fresh lunch tradition here in Oaxaca and have found it particularly gratifying. Not only has Edgar gotten to try foods he’s never had before, I’ve come to learn his likes and dislikes. He is particularly fond, for instance, of a side salad, and when he really likes something I’ll get a comment of “qué rico” (how delicious”) after the meal is over. On one occasion—just one—he took a photo of the food I’d prepared before he started eating. To date, it is the greatest food accomplishment I’ve had since moving here.

Almuerzo for Edgar

It was only a couple of weeks into our time in Oaxaca that Penny said, “Edgar asked if I could talk to you about almuerzo.”

There are days, though, when circumstances require I order in, and that’s what happened this Inauguration Day when Edgar showed up for work as planned, as well as our builders Antonio and Poncho, who arrived a full two weeks early to begin the installation of our spiral staircase.

“Por qué estan Antonio y Poncho aquí?” I asked Edgar after the sound of a honking horn brought me to our front gate.

“Ellos estan aquí para la escalera,” Edgar said. “No sabes este?”

No, I didn’t know they were coming. They’d mentioned they might be available on this date for a different and significantly smaller project, but even that hadn’t been confirmed. But in short order, the two men set about erecting a wall of plastic sheeting to control the spread of dust and began demolishing the floor in our living room, which sits immediately next to the kitchen.

This created a dilemma. We don’t typically feed our workers but over the past year, Antonio and Poncho (his son-in-law) had shown up on short notice to perform emergency repairs. Their work is excellent and inexpensive, and we are incentivized to keep them happy. And besides, when you make a living by cooking and feeding people, there’s something a bit grotesque about preparing and eating a meal in front of two guys kneeling in front of you who are caked in brick dust and fragments of concrete and tile.

“Let’s order in,” I texted to Andrea, and she readily agreed.

My destination was Rosticería May, a rotisserie chicken restaurant that sits on the corner of Highway 190—part of the famed Pan-America Highway that runs from Canada to South America—and the road that leads to San Sebastián Etla, the flat, bustling town one must pass through to reach San Agustín.

Rosticería May is a long, rectangular restaurant with a red plastic awning, white plastic chairs and tables, and a bank of slowly rotating rotisserie chicken machines. It is in many ways unremarkable, one of the thousands of comedors (casual, everyday restaurants) that appear in every part of Mexico. For us, though, it’s a comforting, routine stop, a place where we can get a good meal for very little money that’s guaranteed to leave us with leftovers.

The only downside is that even after a year of placing orders I’m still greeted with minor bewilderment. Every single time I step up to the squat, concrete counter to place an order I’m greeted without even a glimmer of recognition. When I ask for two complete chicken meals (each of which comes with a full chicken cut into pieces, salad, rice, two kinds of salsas, pickled carrots and jalapeños, and hot corn tortillas) they treat me as if they can’t quite believe a gringo would want to eat their food.

Perhaps part of the problem is that they simply don’t understand how good their chicken is, and that’s particularly true of the barbacoa (Mexican barbeque-style) chicken. While the other recipes they offer are certainly flavorful, only the barbacoa chicken is cooked in a vat of spiced, seasoned liquid. Each order is brought to the counter in a steaming white plastic bag damp with condensation, and in with the chicken is a raft of meltingly soft onions that float amongst a sea of bay leaves. Everything is slicked with drippings from the chicken and the aroma is so powerful that if you drove home with your car windows your car would probably be followed by a pack of stray dogs.

By the time I reached Rosticería May I was hungry, but knew that before the quick drive home was over I’d be ravenous. I pulled off the highway at the front of the shop, opened the door to the car, and saw, my heart sinking, that the restaurant was closed. Resignedly I drove to another restaurant where we typically order large styrofoam clamshells filled with cochinita pibil (a type of pit-roasted pork from the Yucatán). They, too, were closed.

I suddenly recalled an offhand comment Edgar had made the day before and texted Andrea.

“EVERYTHING IS CLOSED BECAUSE OF CLAUDIA,” I wrote furiously.

Before I’d left the house I had forgotten a key piece of information: with only one week’s notice, Mexico’s congress unexpectedly made Inauguration Day a federal holiday.

It’s said the move was the result of political maneuvering by Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO), Mexico’s outgoing president, and that the change was motivated by his desire for all of Mexico to be free to witness the election of his protegée, whom a great many people fear will essentially be his puppet. It’s not a farfetched theory.

AMLO is very much a figure of mixed reputation in Mexico. The party he helped to found, Morena, didn’t just unseat the entrenched and corrupt PRI party (which had led Mexico for more than 70 years), over time it also lifted a huge number of Mexicans out of poverty and in many ways helped to modernize Mexican. However, along the way, it also significantly eroded or destroyed several democratic institutions and AMLO himself is decidedly tyrannical, a bombastic and brittle person who craves power and recognition. He has publicly doxxed reporters who have written stories he doesn’t like, it’s said Mexico’s judicial reform is a way for him to harm his rivals before he leaves office, and he’s in general someone who will use every lever of power available to him to elevate both his self-image and that of his political party.

AMLO is the reason October 1st is now a holiday, and Claudia’s election is why, with little notice, every restaurant in town seemed to be suddenly closed.

I was in trouble. My watch said it was already 11:00 am, the time almuerzo (lunch) is typically served, and the guys were waiting for me. There was only one restaurant I thought even might be open, a comedor only a few minutes from our house which serves incredible tortas for only 45 pesos each (about $2.50). I drove there as fast as I safely could and found, mercifully, the woman who runs the shop was behind the counter. Quickly I fired off a text message to Antonio.

“Los restaurantes para pollo y cochinita pibil están cerrados! Voy a comprar tortas, puedo decirles los sabores disponsibles.”

“Ok”, Antonio responded.

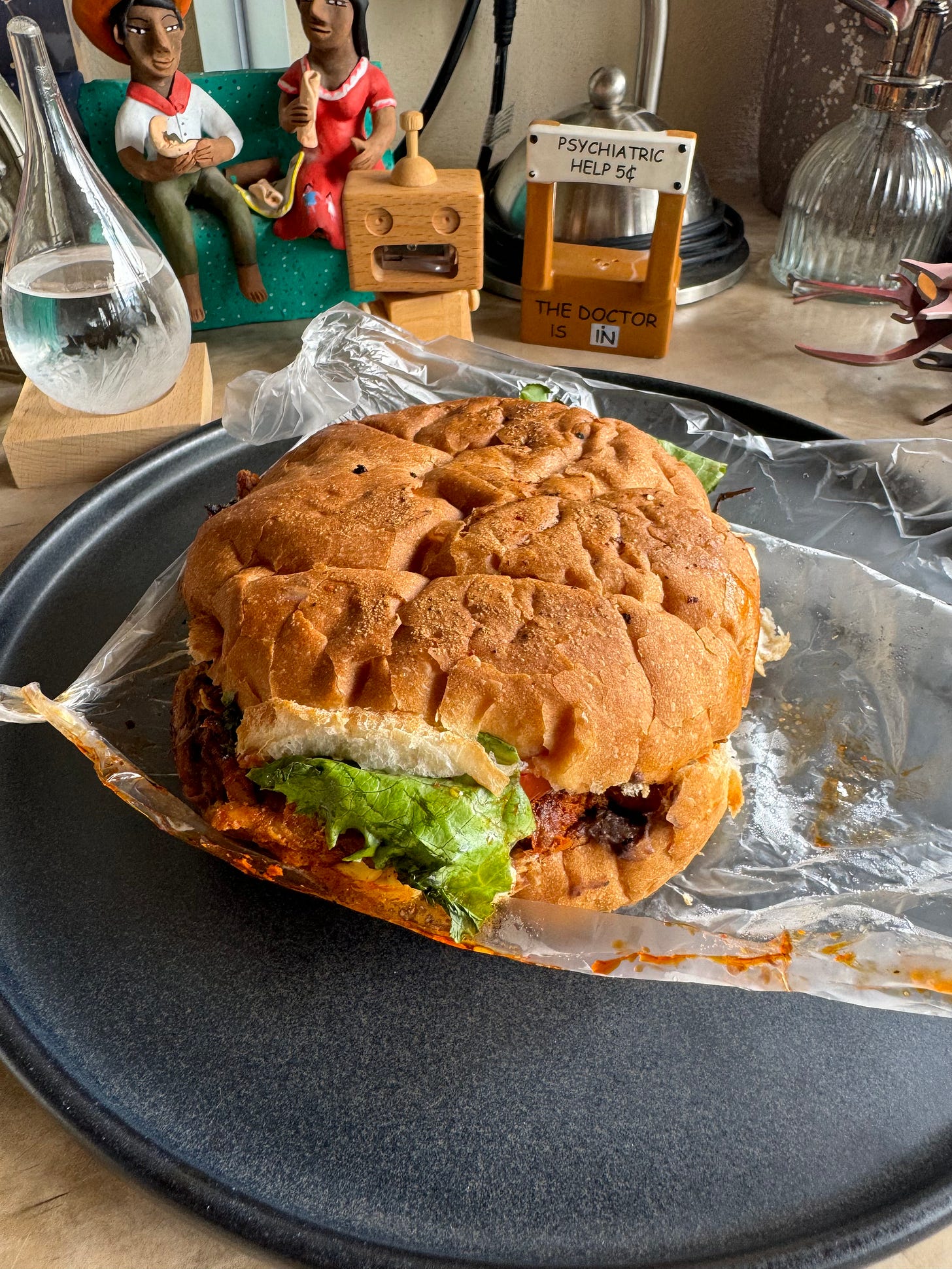

As promised, I asked the woman behind the counter which flavors were available. She responded that she had choriqueso (crumbled Mexican chorizo and melty Oaxaca cheese), Milanese (a fried, breaded chicken cutlet), chile relleno (a roasted poblano chile stuffed with pulled chicken), and cecina enchilada (pork cutlets marinated in flavorful sauce). I messaged Antonio the information about the options and stood in the restaurant waiting for his reply. As I lingered the clouds which darkened the sky began to pelt the neighborhood with pitiful, misty rain.

Suddenly a message arrived from Antonio. “Son grandes o chicas las tortas?”

This was not a question I was expecting. “Creo que grandes,” I wrote hesitatingly. “No es tan pequeño pero no es gigante también. Pero un buen tamaño.” The sandwiches from this particular restaurant are neither small nor gigantic, I wrote, but a good size.

This was not the response Antonio was hoping for and his next message asked for five sandwiches: one choriqueso, two Milanesa, and two cecina.

Five sandwiches! I suddenly felt like a dad with an ungrateful, ravenous teenager. Our offering to buy lunch was an act of generosity, not a requirement, and when I order lunch for Edgar one sandwich is always more than sufficient. Antonio’s message, though, made me flashback to a quick comment Edgar made to me as I was leaving the house. “I think the guys eat a lot of tortillas,” he whispered to me in Spanish. His missed comment wasn’t just an observation, it was a warning.

Once the shock and irritation wore off I realized I was being ungenerous. The cost of the sandwiches was hardly more than we would have paid for the chicken, and the guys’ labor was difficult and done without complaint or breaks. I ordered the sandwiches and soon was home.

Later, at the end of the day, I asked Antonio how much money we owed him for the job. He thought about it for a minute and quoted us a price of 5000 pesos, which is around $260.

$260 for two full days of labor, including the cost of materials, for a job that started two weeks earlier than planned. My realization I was being cheap morphed into a feeling of guilt. $9 to feed these guys was a very small price to pay. That was especially proven true when Edgar said to me, “Tenemos una torta extra.” We had an extra sandwich?

Antonio’s text message order, it turns out, also included a sandwich for Edgar.

Sheepishly, I said to the guys, “Tomas la torta extra.” You take the extra sandwich. A gift, on the house.

A little consideration goes a long way. Lunch today, a friend for life!